A look at the Pedi-Cab (Cyclo-Pousse)

King of the Saigon streets

by Charles Sidilaire

An article published in “Indochine Sud-Est Asiatique” (Southeast Asian Indochina), Number 5, from April 1952.

A monthly magazine sold in France for 150 francs, and 20 piasters in Indochina. Â .

The daily life of the Pedi-Cab driver in Saigon

A Coolie that went up one rung on the social ladder, the Saigon Pedi-Cab driver is commonly called “cyclo”. That gets shortened even more; one cries: “clo” when one hails it in the shady streets where he moves soundlessly, sliding stealthily like a fish in a bowl.

The “cyclo” driver is a seductive individual, if one goes to the trouble to look a little closer. Topped with a shabby felt hat, a worm-eaten colonial pith helmet, or by a bath towel rolled up as a turban, he often wears a threadbare shirt, torn and sweat-soaked. Black shorts show long, muscular, sunburned legs.

On days of heavy rain he goes shirtless with water up to the hubs when the city is flooded for an hour. At those times he laughs out loud under the downpour happily calling to his colleagues, taunting the motorists who are paralyzed because their vehicle’s engine has drowned: the cyclo never stops.

Indeed, the cyclo is the king of the pavement, an uncontested king who, in the stifling heat of the 11th parallel, makes the rules. The street is his, pedestrians and motorists need to just hang on when he blissfully crosses intersections.

Every passing man or woman is potential prey for the cyclo. When he prowls, he seems to be sleeping in the saddle, with but one foot on his machine’s pedal. But his eye, his small and sparkling black eye, set in its almond-shaped socket, watches. Much like a snake following its victim.

Variants of the hats worn by the cyclos: Colonial helmet, soft felt, bath towel rolled up as a turban, cone-shaped hat made from Latan palm leaves.

Their status seems to compel them to avoid new headgear, and imposes a faded cover, worn by sun and rain.

The cyclo distinguishes himself by his ability to navigate through traffic without worrying about the road.

He tests the crowd, attracts the attention of the hurried or exhausted passer-by with an imperceptible movement of the eyelid, or with a large hand gesture. Three out of ten times the customer takes the bait and allows himself to be ensconced on the seat.

Then the cyclo comes to life again. An unsuspected energy spreads throughout his limbs. His eagerness is such that before even knowing the destination he’s already going at a good clip, straight ahead. He’s so fast that he’s suspected or blamed for most traffic accidents.

In principle, every Pedi-Cab driver must have a driver’s license, issued by the municipal police following a test on the basic knowledge of the rules of the road and the operation of the machine. In practice, only 30% of the cyclos are licensed. The companies which take pride in hiring only licensed drivers are the minority.

The cyclo is so zealous that French customers who are not familiar with the layout of Saigon often take a tour of the city before reaching their destination which was 100 yards from their departure point. There are terrible misunderstandings: only half of the 6,500 cyclos in Saigon understand French.

To be a good cyclo one must have the constitution of a horse. The cyclo really accomplishes a huge task, even though the gear ratio of his machine is very low, lower than a bicycle since it is made up of a 22-tooth sprocket in the rear and 32 in front. To stay in shape the cyclo stops four, five, or six times a day at the stands of mobile food vendors, where he finds renewed strength in the Chinese soup and rice, the basis of his nourishment.

The cyclo can, from some viewpoints, be considered to be a real workhorse. He rents his vehicle from an entrepreneur for a price which varies from 18 to 21 piasters a day, depending on the company. Of course there is no limitation to how much time he can work. It’s up to him to do overtime, or to put in time at the sugar-cane press or at a mobile restaurant.

Additionally, the exact accounting of the daily take of a cyclo is difficult. It all depends on his enthusiasm for work. Add to this the fact that some days are more lucrative than others, especially in the rainy season. The declared figures can have but an appreciative value. Nevertheless, one can estimate that a good cyclo can earn an average of 50 to 60 piasters a day. Things get complicated when one takes into account the “clandestins”.

Indeed, quite frequently a cyclo, having rented a pedi-cab from a company, will then indulge himself in the speculative pleasures of sub-letting. It even happens that the sub-letter will again sublet the machine that he sublet for the afternoon. Needless to say, the profit margin decreases with each deal, but everyone gets something out of it. It is estimated that the 6,500 pedi-cabs of Saigon-Cholon-Giadinh provide a living for nearly 12,000 drivers, professionals as well as amateurs.

In the struggle for life, the cyclo quite simply appropriates his customers. He takes an authoritative option on their trips, finds their address, takes note of their schedule, and strives to keep away competitors, who also have respect for this sort of control over the customer.

Rarely do the cyclos argue over “business”.

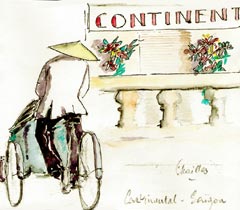

A pedi-cab next to Continental Hotel

by Escailles

With respect to the customers he has adopted, the cyclo can have endearing qualities. If the roadway is bad he’ll carefully avoid ruts. Caught in a traffic jam, he’ll energetically demand the right-of-way. He’ll even go so far as to extend credit although in the end he scarcely earns more than 20 piasters per day.

A number of cyclos keep their machine at home at night – when they have a home. Otherwise they sleep on the machine or next to it, on a camp cot in the street.

Muscular legs for work, the customer seat for a nap, a few more piasters to lose gambling; the cyclo often has no other ambition. .

Pierre Coupeaud

A Phnom Penh industrialist, inventor of the Pedi-Cab

He appeared for the first time in Phnom-Pehn in 1937.

The industrialist creator of the vehicle, Pierre Coupeaud, was originally from the Charente (region of France), and lived in Phnom-Penh.

Athletic and tenacious, he would have to fight to have his creation recognized by the civil authorities, in this case the Public Works Department.

The ministry only gave its formal approval for the use of this intrepid means of locomotion after having entrusted the new contraption to a couple of experienced “velocipedists”, Speicher and Le Grèves, heroes of the Tour de France.

Trial runs were held in Paris, on the wide paths of the Bois de Boulogne. In the end, the champions congratulated the ingenious Charenter. Appropriately, the prototype was christened with Pineau des Charentes (an aperitif). The capital of Cambodia finally gave citizenship to the Pedi-Cab.

In the photo on the left, in the dry season they sleep in the open. Some sleep on a mat, the more privileged on camp cots near their vehicles.

In the photo on the right, a French soldier on a Pedi-Cab.

In the photo on the left, two Pedi-Cabs in the 60's.

In the photo on the right, a Pedi-Cab in the famous Sailor’s Street (rue des Marins) in Cholon.

The conquest of Saigon.

Before long, Pierre Coupeaud went off to conquer Saigon. In 1939 he took off on a Pedi-Cab driven by two coolies who relayed one another. It took him seventeen hours and twenty-three minutes to cover the 200 kilometers that separate the two capitals. His arrival was quite spectacular, in the middle of a bicycle race.

Despite the success that lay ahead, the mayor of Saigon, while convinced of the soundness of the machines, would in turn be cautious. As a test, he began by authorizing the commissioning of twenty cyclos. Local columnists commented extensively and favorably on the future of this new mode of transportation.

A Vietnamese man named Bay Vien (the Master of Cholon) and a Frenchman named Maurice monopolised cyclo services around the Cholon Market with over 30 cyclos.

In fact, the Pedi-Cab took ten years to eliminate the antique “pousse-pousse” or rickshaw.

The figure of 6,500 Pedi-Cabs seems low, if one considers that the region of Saigon-Cholon numbers a million seven hundred thousand residents by itself. But the specialists in the matter, in this case the Pedi-cab companies themselves, maintain that the balance between supply and demand has been reached, and that there is no need to add more vehicles to the fleet. The cyclos, to whom the elementary laws of economics are quite clear, feel that there are enough of them. Add to this the fact that recruiting for this particular type of laborer has now become quite difficult.

The arrival of the cyclo-motor

Indeed, young people have found something better than the cyclo: its direct descendant, the cyclo-motor. Already the battle has begun between the two rival machines. Eighteen hundred cyclo-motors today face 6,500 cyclos. They have the advantage of gaining in distance but they are despised for their intolerable noise.

The cyclo-motor’s day often ends in Cholon, around the gaming tables. A demon drags man to the false illusion of wealth. Until late at night, he watches luck with the same patience he employs in stalking customers. If customers are frequent, luck, on the other hand, is scarce. All too often, the 20 hard-earned piasters end up in the hands of the dealer.

However, one would be wrong to believe that gambling is the downfall of all the cyclos. Some are well-organized citizens, who look out for the education of their offspring such as the cyclo whose daughter is studying in a high school in Saigon. For her at least, her father’s sweat has paid off...

At the end of the '30's Pierre Coupeaud owned a company at 147 Galliéni Street in Phnom-Penh.

At the end of the '40's he was also the owner of its plants located at:

6 Marne Wharf (now bên Vân Dôn)

Saigon

>

>